Today the prospects of a drop as big as 1988 have already sent prices about 50% higher since June. The difference of

course is the markets are much more sensitive now to supply shocks. I'm not an

economist (my standard excuse) but from what I can tell it has a lot to do with

low stocks, which in turn has a lot to do with ethanol and other inelastic

sources of demand. So the question about a new normal is also partly about whether the market situation is the new

normal. I'll leave it to the real economists to answer that one.

Friday, July 27, 2012

The New Normal? Part Deux

Following on my earlier post, another way of thinking about

normal is not just the conditions on the supply side, but on the demand side. The

last big drought we had, in 1988, caused a 25% drop in supply, but barely a

blip in corn prices.

The New Normal?

Talking to journalists over the past week about the drought,

I think the most common question I get is whether, because of climate change,

what we are seeing should be viewed as the new normal. My answer is no and yes.

At that point I can almost hear them mumbling "can't an academic ever give a

straight answer?" So let me explain.

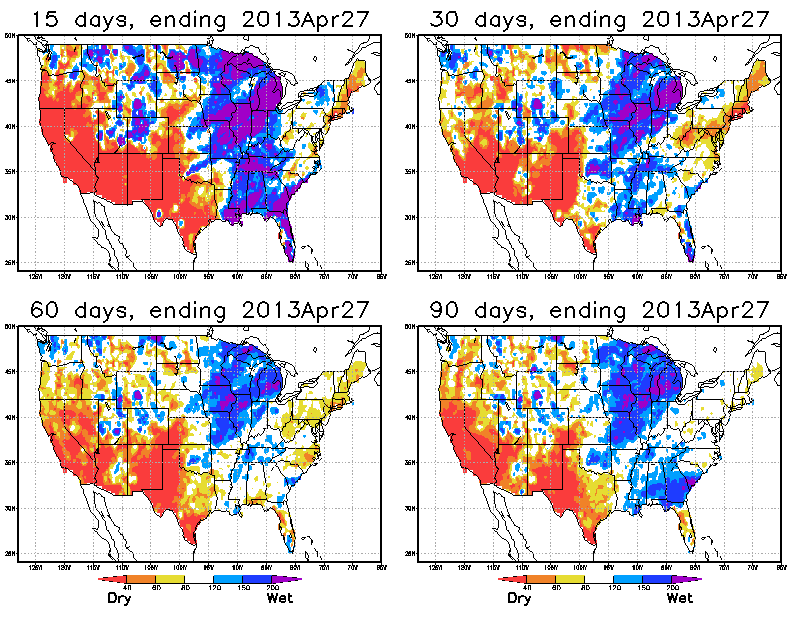

The no part relates to rainfall. There's been really low amounts of

rainfall in most parts since the spring, in many places 50% or less of normal. Below

is a summary from NOAA.

The nice plots that Wolfram posted show that this year is

not quite the most extreme in the past 50 years, but it is close. From climate

model projections, we know that even the most extreme models don't get a change

in average rainfall by 2020 or even 2030 that is even close enough to bring

average rainfall to the historic lows. In fact, it's very rare to see changes

that big even by 2100. For example, the figure below from IPCC shows each

climate model’s projection of precipitation change by the end of the century.

Only one or two show changes of more than 30% in the Corn Belt, and that’s by the end of the century.

Or if projections aren't your thing, just look at observed

trends. There is almost nowhere in the world where precipitation trends are

bigger than what one can explain just by natural variability. We highlighted

this in a Science paper last year focused on agricultural areas. So the bottom

line is this is an unusually low rainfall year, and it would still be unusually

low if it happened 20 years from now.

Temperature is a different story. Most agricultural areas

have seen trends since 1980 of about two standard deviations. That means that

an average year now is like a very hot year back in 1980. The US had been an

exception to this rule (again see paper), but that was most likely natural variability masking

the trend, and there's no reason to think that will continue. For example, a

nice analysis by Gerald Meehl and colleagues shows that climate model

simulations that reproduce the "warming hole" show just as rapid

warming in the 21st century as other models.

This year so far is very warm, but not completely unprecedented

in terms of extreme heat, at least not yet (as Wolfram’s plot showed). Without

any detailed calculations, I would guess this year is a little warmer than what

we should normally expect over the next decade, but not that much. Maybe it’s

the new normal for 10 or 20 years from now.

So the best I can say is that a year like this will be more

common moving forward. If I'm interpreting "normal" literally, as in

an average year, then i don’t think it’s fair to say this is the new normal

because rainfall is so low. But years with such high heat and low soil moisture like this won’t be so rare, and we

shouldn’t be surprised to see them more often. Especially now that the

"mask" of climate variability seems to have been taken off.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)