I've often panned the idea that commodity prices have been greatly influenced by so-called financialization---the emergence of tradable commodity price indices and growing participation by Wall Street in commodity futures trading. No, Goldman Sachs did not cause the food and oil-price spikes in recent years. I've had good company in this view. See, for example, Killian, Knittel and Pindyck, Krugman (also here), Hamilton, Irwin and coauthers, and I expect many others.

I don't deny that Wall Street has gotten deeper into the commodity game, a trend that many connect to Gorton and Rouwenhorst (and much earlier similar findings). But my sense is that commodity prices derive from more-or-less fundamental factors--supply and demand--and fairly reasonable expectations about future supply and demand. Bubbles can happen in commodities, but mainly when there is poor information about supply, demand, trade and inventories. Consider rice, circa 2008.

But most aren't thinking about rice. They're thinking about oil.

The financialization/speculation meme hasn't gone away, and now bigger guns are entering the fray, with some new theorizing and evidence.

Xiong theorizes (also see Cheng and Xiong and Tang and Xiong) that commodity demand might be upward sloping. A tacit implication is that new speculation of higher prices could feed higher demand, leading to even higher prices, and an upward spiral. A commodity price "bubble" could arise without accumulation of inventories, as many of us have argued. Tang and Xiong don't actually write this, but I think some readers may infer it (incorrectly, in my view).

It is an interesting and counter-intuitive result. After all, The Law of Demand is the first thing everybody learns in Econ 101: holding all else the same, people buy less as price goes up. Tang and Xiong get around this by considering how market participants learn about future supply and demand. Here it's important to realize that commodity consumers are actually businesses that use commodities as inputs into their production processes. Think of refineries, food processors, or, further down the chain, shipping companies and airlines. These businesses are trying to read crystal balls about future demand for their final products. Tang and Xiong suppose that commodity futures tell these businesses something about future demand. Higher commodity futures may indicate stronger future demand for their finished, so they buy more raw commodities, not less.

There's probably some truth to this view. However, it's not clear whether or when demand curves would actually bend backwards. And more pointedly, even if the theory were true, it doesn't really imply any kind of market failure that regulation might ameliorate. Presumably some traders actually have a sense of the factors causing prices to spike: rapidly growing demand in China and other parts of Asia, a bad drought, an oil prospect that doesn't pan out, conflict in the Middle East that might disrupt future oil exports, and so on. Demand shifting out due to reasonable expectations of higher future demand for finished product is not a market failure or the makings of a bubble. I think Tang and Xiong know this, but the context of their reasoning seems to suggest they've uncovered a real anomaly, and I don't think they have. Yes, it would be good to have more and better information about product supply, demand and disposition. But we already knew that.

One piece of evidence is that commodity prices have become more correlated with each other, and with stock prices, with a big spike around 2008, and much more so for indexed commodities than off-index commodities.

This spike in correlatedness happens to coincide with the overall spike in commodity prices, especially oil and food commodities. This fact would seem consistent with the idea that aggregate demand growth--real or anticipated--was driving both higher prices and higher correlatedness. This view isn't contrary to Tang and Xiong's theory, or really contrary to any of the other experts I linked to above. And none of this really suggests speculation or financialization has anything to do with it. After all, Wall Street interest in commodities started growing much earlier, between 2004 and 2007, and we don't see much out of the ordinary around that time.

The observation that common demand factors---mainly China growth pre-2008 and the Great Recession since then---have been driving price fluctuations also helps to explain changing hedging profiles and risk premiums noted by Tang and Xiong and others. When idiosyncratic supply shocks drive commodity price fluctuations (e.g, bad weather), we should expect little correlation with the aggregate economy, and risk premiums should be low, and possibly even negative for critical inputs like oil. But when large demand shocks drive fluctuations, correlatedness becomes positive and so do risk premiums.

None of this is really contrary to what Tang and Xiong write. But I'm kind of confused about why they see demand growth from China as an alternative explanation for their findings. It all looks the same to me. It all looks like good old fashioned fundamentals.

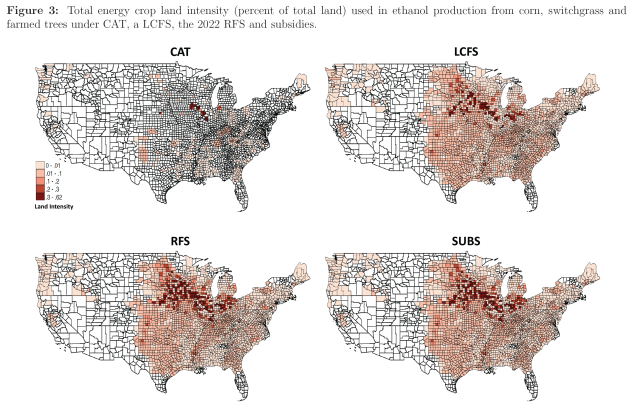

Another critical point about correlatedness that Tang and Xiong overlook is the role of ethanol policy. Ethanol started to become serious business around 2007 and going into 2008, making a real if modest contribution to our fuel supply, and drawing a huge share of the all-important US corn crop.

During this period, even without subsidies, ethanol was competitive with gasoline. Moreover, ethanol concentrations hadn't yet hit 10% blend wall, above which ethanol might damage some standard gasoline engines. So, for a short while, oil and corn were effectively perfect substitutes, and this caused their prices to be highly correlated. Corn prices, in turn, tend to be highly correlated with soybean and wheat prices, since they are substitutes in both production and consumption.

With ethanol effectively bridging energy and agricultural commodities, we got a big spike in correlatedness. And it had nothing to do with financialization or speculation.

Note that this link effectively broke shortly thereafter. Once ethanol concentrations hit the blend wall, oil and ethanol went from being nearly perfect substitutes to nearly perfect complements in the production of gasoline. They still shared some aggregate demand shocks, but oil-specific supply shocks and some speculative shocks started to push corn and oil prices in opposite directions.

Tang and Xiong also present new evidence on the volatility of hedgers positions. Hedgers--presumably commodity sellers who are more invested in commodities and want to their risk onto Wall Street---have highly volatile positions relative to the volatility of actual output.

These are interesting statistics. But it really seems like a comparison of apples and oranges. Why should we expect hedger's positions to scale with the volatility of output? There are two risks for farmers: quantity and price. For most farmers one is a poor substitute for the other.

After all, very small changes in quantity can cause huge changes in price due to the steep and possibly even backward-bending demand. And it's not just US output that matters. US farmers pay close attention to weather and harvest in Brazil, Australia, Russia, China and other places, too.

It also depends a little on which farmers we're talking about, since some farmers have a natural hedge if they are in a region with a high concentration of production (Iowa), while others don't (Georgia). And farmers also have an ongoing interest in the value of their land that far exceeds the current crop, which they can partially hedge through commodity markets since prices tend to be highly autocorrelated.

Also, today's farmers, especially those engaged in futures markets, may be highly diversified into other non-agricultural investments. It's not really clear what their best hedging strategy ought to look like.

Anyhow, these are nice papers with a bit of good data to ponder, and a very nice review of past literature. But I don't see how any of it sheds new light on the effects of commodity financialization. All of it is easy to reconcile with existing frameworks. I still see no evidence that speculation and Wall Street involvement in commodities is wreaking havoc.